Posted by Susannah on Feb 26, 2012 in

Motherhood,

Musings

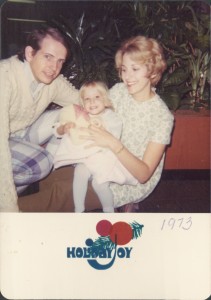

My first family Christmas photo

I’m embarrassed to say that I’m finally getting the last of the random pieces of Christmas put away. A month or so ago, the Christmas decorations were unceremoniously stashed into a heap in the basement. ‘Out of sight; out of mind’ allowed me to procrastinate even further. Finally, however, everything is organized and stacked in passably neat boxes in the corner of the basement. The only thing left is a pile of Christmas cards, which are actually still on the mantel.

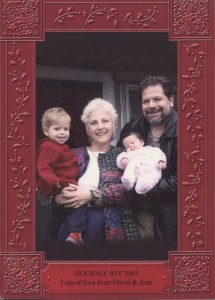

I guess the cards linger because the real tradition I cling to is the Christmas card. Those memories go as far back as I can remember. There are people who have received a card from my mother every year since I was born. And it’s always been a photo card. Thankfully, she’s finally released my sister and me from being the stars of the card. We owe her relinquishment to our children, who now occupy center space on the family photo cards.

I must admit to having ambivalent memories of taking the Christmas card picture as a kid, especially in our teen years. If I could get my older sister to chime in on this one, we’d probably go on way too long.

Although we often took the picture on Thanksgiving, if there was an early Pennsylvania snow, we knew it would mean bundling up and getting our smiles and knitted grandmother sweaters on before the heavy, wet snow fell off the pine trees. We’d pose for frame after frame depicting tender and joyful sisterly love.

Portrait of the perfect family.

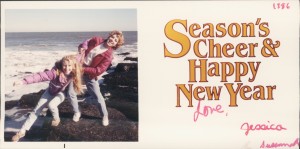

Jessica and me--the portrait of sisterly love

Isn’t that what the holiday card is all about? I don’t think it’s necessary to hash up the past, and I know my mother may be saddened to see this in writing, but there was nothing that would crush the holiday spirit more quickly than the hassle of trying to take that Christmas card picture. After shooting a full roll, we’d rush over to the store to get it developed and hope for the best. There were no digital pictures back then, so we would have to wait days before learning if the shot was Christmas card worthy. A fake smile, double chin, closed eye, or the accidental arrangement of a telephone pole would mean starting back at square one. Of course, technology moved us forward, though sometimes not in a good way. I remember a particularly weak card one year where we actually photoshopped in my sister. Unfortunately, the technology just wasn’t quite where it needed to be.

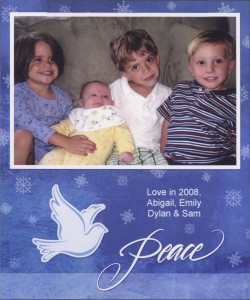

Today, however, as I now have children of my own and have continued my mother’s tradition of sending photo cards that chronicle Dylan’s and Abigail’s lives, I see a different side of it all. Christmas cards are a perfect platform to keep connected with friends that you may not have seen in years. It’s an active way of saying, “I still think of you.” It stands in high contrast to the way in which we have all become voyeurs to the lives of practical strangers on networks like Facebook where our ‘friends’ number in the high three and even four digits.

Kids and Cats

The Christmas card is a perhaps more antiquated version of our modern social networking outlets. It’s like a once-a-year Facebook post on the family. We announce new babies, new marriages, new homes, and new jobs. We chronicle our family trips, promotions, All-Star teams, ballet classes, home upgrades, prestigious college admissions, passions for everything princess, honor rolls, potty training success, new pets, dead pets, new careers, mom’s first girls’ weekend, broken legs, and birthday bashes. . . . The Christmas card is the perfect place to put forth each family’s “ideal self.”

And I guess that it’s a good thing that no one really tells it like it is. Imagine getting this on a card: “Kelly has started to struggle with self-induced vomiting and has dabbled in drug use. Joey finally got diagnosed with ADHD and aggression issues after stabbing three other children with a pencil. And Gary and I have broken into the kids’ college fund to pay for rehab and marital counseling after he found himself with over $12,000 worth of charges from online porn sites.”

Tom-foolery: our way of rebelling against the dreaded "Christmas card photo"

Yeah, it’s mostly just the good news. Although there is sad news that can’t be sugar-coated or avoided. Christmas cards force me to face the heartbreak. One card we received shared the tragic news of a life-changing injury sustained by a dear friend’s husband while serving in Iraq a few years ago, explaining why we had not heard from the couple in a several years. They’re just now starting to send cards again. Another card we sent, addressed to a couple, was answered with a phone call sharing the sudden loss of a husband this past summer. And the sadness can’t be more poignant each year when we see a little halo over the name of a friend’s baby who died of SIDS five years ago.

And there’s the unavoidable news of name and address changes brought on by divorces. My husband claims I have more divorced friends than anyone he knows. I’m not sure about that, but I do know that each year, there are one or two new splits to add to the list. Of course, there are other couples where we are more surprised to see that they are still together year after year. It does make me wonder sometimes what bets are placed on my husband and me. . . .

Mom Finds New Subjects: The Grandkids!

So for me, it’s not a bragging letter, the picture, or the foil-lined envelopes. Instead it’s the poignant moments that come when I’m going through the list in January, editing and updating. I sort through the envelopes, updating and correcting my list. I remember my mother doing the same, though with the advancement of technology, I do it a little differently. She had a flowered address book, with addresses written in pencil so new addresses and changed names could be easily edited. Albeit impersonal, I now I use an Excel spreadsheet.

As streamlined as my system is, it begs the question of what to do when someone dies. For my mother, when someone died, she’d just put ‘dec.’ and the date. She never erased a name. But since I use the spreadsheet, instead of a little note by the name like my mom did, I delete the deceased spouse, making it ‘address ready.’ This year, I was overcome with the harshness of it all.

So for 2012, I added a few babies, changed a handful of addresses, inserted a few rows to accommodate where one household had become two, and added a Mr. & Mrs. to a few lines. But the hardest change was when I deleted my Aunt Amy’s name last week, who succumbed to cancer a few months back. Though I’ll continue to send a card to her partner, her own name was now gone from my list. No pencil mark “dec. 10/26/11” like I remember seeing in my mother’s tattered Christmas address book. Although I know the feelings of loss and change are still the same, at that moment, the process felt overcome by mechanization.

Maybe that’s why my cards are still on the mantel in the little snowman card holder my kids made for me. And I guess I’ll keep them there as long as it takes to shed those tears that still seem to come out of nowhere when I think of Aunt Amy, and that will eventually be tempered by remembering all the fun times with her and her consistently artistic and ‘laugh out loud’ funny photo Christmas cards.

And I’ve decided to make some changes on my Excel spreadsheet Christmas card list, too. Instead of deleting grandparents and favorite aunts’ names, I’m going to insert a column, right after the address. I’ll simply cut and paste each lost loved one’s name to this new column, and label it “dec.” at the top, as a nod to my own mother’s wise ways.

A new generation of family models

I’ll also try to find more balance —the more technology that’s available, the more my life is convenient and streamlined. But with these advancements comes the need to guard against being overcome with the soullessness of it all. No technology can ever fill the void left when that last Christmas card from a loved one is opened. In fact, with all the scientific advancements, we still can’t predict just when it will be that last card. Maybe that’s why the cards linger on the mantel. I have a need to hold onto something more tangible than an Excel spreadsheet on a blinking screen. Instead I have the smiling photo cards, the sweet handwritten signatures of small children, and the understanding at last of the necessity, on some level, to preserve a “perfect” past. It helps us cope, you see, with a sometimes imperfect present where heartbreak is real.

Posted by Susannah on Jan 15, 2012 in

Motherhood,

Musings,

Travel Archives

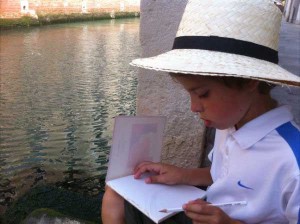

My daughter drawing leisurely in Venice

As I sat on the steps outside the Musee d’Orsay, listening to the click and swish of the street performers’ roller skates, it sadly dawned on me that I would once again miss the inside of the museum. No wandering through the majestic corridors or getting lost in the muted colors of Monet, Manet, Degas or Renoir.

Instead, just a few yards away from the museum entrance, I was sitting on grotty steps, watching a pair of street performers, one testing the limits of roller skates and the other whose gig was to mock innocent passersby. My kids were reduced to falling over in giggles every time an unsuspecting tourist was victimized. It was entertaining, but I couldn’t deny the call of the French Impressionists. I was counting down until closing time. Thirty eight minutes left. How had inertia anchored me here, in Paris of all places?

You see, I had never liked Paris. The only reason I came this time was out of a sense of duty. My husband loved Paris, and since he couldn’t join us on this part of the trip, I felt compelled to include Paris in our summer itinerary. It was a nod in his direction, a feeble recognition of what he had done to make this trip possible. After we had traveled together for the past month in Spain and Morocco, he flew home, and the kids and I headed off to get a taste of the rest of Europe, wandering through five weeks of Germany, France, Italy, and Austria. My husband acted as our ‘stateside support ,’ researching hotels, making reservations, and paying the bills, of course.

So it was just the kids and me. And Paris. Which I hated. I hated the rainy weather, the expensive food, and the unfriendly shopkeepers. And I hated the promise of Paris. The romance. The lure of the Eiffel Tower. This was my fourth trip to Paris, and I again swore it would be my last.

My kids with crepes in Paris

The first time I was in Paris, I was in high school. It was the spring break language trip. The weather was chilly, and my experience couldn’t compare to that of my Spanish-studying classmates who were spending a fabulous time on the sultry Iberian Peninsula. Not yet 21 and under the constant scrutiny of chaperones, I and my classmates couldn’t even find much pleasure in the realization that wine was, in fact, cheaper than Coke. And it was more than just the Coke that seemed expensive on a babysitter’s budget. Even though it was the 90s, and the Euro had not yet taken over, I probably only had a few hundred bucks for the week. That could last one meal in a metropolitan city like Paris and wouldn’t get me very far in the much anticipated French boutiques. Even kitschy souvenir shopping, which suite my budget better, was a lackluster experience. The unaccommodating shopkeepers rebutted my attempts at speaking diligently practiced high school French. Either I received a blank stare or a curt, tight-lipped, “Excuse me?” in perfect English.

My second foray among the Parisians was definitely a notch up. It was a 21-day, whirlwind tour of Europe with my mother and sister. I could enjoy the cheap wine, had a bit more money to shop, and relaxed at many mediocre pre-arranged meals. But my memories are vague. It was a quick trip. Eiffel Tower, Monaco Casinos, Coliseum, Venice Canals, the Alps, Schoenborn Palace, Goldenes Dachl, Neuschwanstein Castle. . .just like the movie.

I haven’t thought of my third trip to Paris in years. I guess I’ve blocked it out. That time, I was in my final semester of college, doing my student teaching at an English-speaking school in Germany. A group of us drove to Paris for the weekend. Imagine that. Driving to Paris for the weekend. I do remember being distinctly impressed with the compactness and ease of travel afforded to the Europeans. But I was once again not impressed with Paris. This time, I was too hung up on love. As I stood on the precipice of Place du Trocadero, with a perfect view of the Eiffel Tower at night, I was with a man with whom I was less than in love. As I tried to force a meager enthusiasm for my date, I vowed never to return to Paris without genuine love. I can’t remember the details, but there were probably a few forced kisses. After all, we were in Paris. It was our last date.

My daughter boat pushing in Paris

But this trip was different. Finances and weather weren’t going to put a damper on this journey. I was ready to take on Paris. I was armed with a rain coat, a few umbrellas, and weather proof shoes. I had plenty of cash and credit. Of course, with two kids, I was not remotely interested in sitting through a five-course meal for three hours or shopping in expensive boutiques, but I could comfortably order a meal in a restaurant for the three of us and buy as many Eiffel Tower key rings as we could carry.

The rudeness of Paris didn’t faze me this time either. Paris is just another big city. I don’t think Parisians are particularly more discourteous than those residing in other big cities of the world. Sure, there’s a bit more snobbery in Paris. Though, at this point in my life, after having crossed the globe a few times, I would give a bit more leeway for Parisian snobbery. It is an impressive city. I guess I also have a tougher skin. Curtness doesn’t bother me as much anymore. I myself have become more practiced at stone cold stares. I was an eighth grade school teacher, have been married for thirteen years, and have a ten and an eight year old. Sarcasm, silent stares, and snooty looks are just a few of the nasty tricks that I’ve acquired. I can raise an eyebrow with a snide lip as good as any Parisian.

And finally, love was no longer an issue. I had traded in my glass slippers for Saucony running shoes, with an occasional high-heeled black leather boot slipped on for fun. Stability, fidelity, and the rewards for working at love were now my priorities. It’s not that my life had become devoid of romance, but that it no longer needed the backdrop of the Eiffel Tower. A simple Saturday morning when the kids slept past 6:30 and we had a few more minutes together would kindle a romantic trajectory that would last through waffles, soccer, an afternoon birthday party and grilled burgers, until the kids were tucked in for the night. At that point, Eiffel Tower or not, we may or may not find ourselves too tired to go on.

So that’s where I found myself in Paris for the fourth time. My conditions were different, but in my estimation, the city hadn’t changed. Arc de Triomphe, Sacre Coeur, Tour Eiffel, and of course, the Louvre.

We had spent a morning in the Louvre. It was a brief visit. We rented the museum guides, walked around for a few hours, and ended up in the Louvre café. I knew the next five weeks would be full of museums, cathedrals, palaces, and long walks. Spending only four hours in the Louve felt like a travesty to me, but the goal of the trip wasn’t to present a concise history of Eastern and Western civilization gleaned from a museum. Instead, it was merely to launch the kids on a life of travel. Two days or even one full day in the Louvre is certainly not the most effective way to infect them with the travel bug.

We walked out of the museum and found ourselves in the Tuileries Gardens. Little did I know that this path would set the tone for the rest of our summer.

Slinging wet pea stones in their wake, both children raced down the garden path to the man with the toy boat cart. They begged for a boat. Exhausted, I collapsed on a chair by the concrete pool. I knew there was a lot more of Paris to see over the next five days, and I suppressed the nagging guilt I felt about ‘giving up’ for the afternoon.

It was two Euros to rent a boat for an hour. The children were given a pole and a boat with a sail. The French-speaking boat peddler, a strange but satisfyingly friendly cross between a gentle grandfather and a homeless man, was accommodating, letting the children choose their boat, suggesting the fastest boats among his collection, and helping them with their first launch.

At that moment, although I wanted to keep hating Paris, I felt my grip loosening. This distaste had taken years to cultivate. I wouldn’t even deign a meal in a French restaurant back home if I could avoid it. It was simply a principal to me now: a snobbery about being snobby.

But this moment challenged every bit of Paris that I found detestable. It was friendly, accommodating, and an undeniably good deal. I had more than two content children, a reclining chair by the fountain, and a spectacular view in every direction. As I sat there for the afternoon, sometimes lost in my thoughts and much of the time thinking nothing at all, I realized I had never let myself completely go in Paris. I had posed for pictures in front of the Eiffel Tower, bartered for the prerequisite Eiffel Tower key rings, and had hung on to a Sorbonne University t-shirt, buried somewhere in my bottom drawer at home. But I had never released my Type A American intensity to become a part of the scenery.

As I melted into the background of tourists photos, I began to see how unimaginably beautiful the city was. How had I missed this on my visits to Paris? I started to look around, to notice the architecture. I absorbed the dampness of the gardens, imbued with the graceful sculptures and aged trees that have literally seen history unfold. And as I sat there, I even began to dismiss the quirky ways of the Parisians, and appreciate the annoyance of the pandering demanded by tourists.

Of course, it did rain for a few minutes that afternoon, but somehow it didn’t matter. The wind and brief moments of pelting rain made the boating all that much more exciting.

I realized that traveling with children affords a certain amount of freedom. Freedom to sit and watch the street performers instead of wandering through high-ceilinged galleries. Freedom to eat crepes for lunch. Freedom to skip the afternoon at the Louvre with the great masters, and instead, become one of the scenes of the great masters: Boy Pushing Boat at Fountain.

As I sat there, I also realized I had never really thought of the goal of our trip. After all, what goal do you need when you’ll be spending the summer in Europe? Pictures of us for the Christmas card in front of the Eiffel Tower, the Grand Canal, and at the top of the Alps? But maybe it was about more. As I watched tourists take photos of children, my children, push-boating in the fountain, maybe this trip was destined to be one where we didn’t see everything, but we instead became a part of everything.

I never did make it into the Musee d’Orsay that afternoon, but I did make the conscious choice to become a part of every place we visited. No check lists, ‘top ten’ lists, or ‘must see’ sights.

Instead, we visited the same little pizza shop in Rome almost every afternoon and got to know the owner’s name and all about his family. Each kid had their favorite stool and type of pizza.

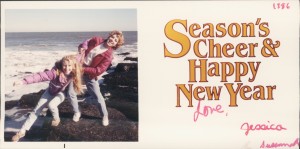

My son drawing in Venice

We went hiking in the Alps with a German family that my daughter had befriended on the train, spending the next two days sharing meals, Prosseco, and the common struggles of raising kids, balancing work and family, and the German perspective on the dilemma in financial markets.

We fed the pigeons at Notre Dame, scattering our leftover baguette from lunch. We never made it to the top of the bell tower in Notre Dame, but no one complained about missing it. They did complain when we ran out of bread, and then the birds wouldn’t eat the gummy candy they foisted on them.

I did my share of eating too—from croissants to gelato. I even ate brats and drank beer at a playground in Kaiserslautern, and at every other playground I found after that day that served them.

There were poignant moments, too. Things came up that I wouldn’t have necessarily brought up with my kids. At the bus stop for the Appian Way, we talked with a Roman who was fiercely racist, protecting his job and lifestyle from North African immigrants. The children listened quietly, and after we parted from him, we spent many hours talking about racism, prejudice, jobs, and country, as we walked from one catacomb to the next.

In Venice, we passed an afternoon with a researcher who was working on an international project on chickens. She was studying how interbreeding chickens actually made them more resistant to disease, more attractive, and provided a lower mortality rate. The children didn’t miss connecting her research to our Appian Way talks about racism and prejudice.

Of course, I could go on. There were so many moments of connections. But this year, although our Christmas card did contain the requisite posed picture in front of a recognized site, it also showed a snapshot of my daughter sketching by the canals of Venice and my son pushing his boat with a pole, raggedy boat-man in the background. I’m not in the photo of course, but I can see my empty green chair, reclining by the fountain pool, where I was sitting when I became a part of the background of Paris.

Posted by Deborah Huso on Dec 30, 2011 in

Musings,

Relationships,

Success Guide “Perfect isn’t that interesting to watch. In fact, it can be both boring and exhausting. What we like to see is human.” –Frances Cole Jones

In a book I had to review recently, the author wrote, and not necessarily with contempt, that social media has made us all exhibitionists and opened the way for everyone to make public confessionals. There is truth in this. And the result is a lot of noise in a world already overflowing with information.

When I asked some women friends and acquaintances to help contribute to this blog, they balked (even the two who are currently contributing). The idea of flinging their personal lives onto the Internet for their parents, their friends, their neighbors to read…and judge…seemed a little bit scary. “What if I offend someone? What if I make someone mad?” Of course, having been a journalist and columnist for many years, I know that stirring up the pot is often the whole point. If you’re not offending someone or making someone mad at least some of the time, you probably don’t stand for much, and you’re probably not making much of a difference in anyone’s life either.

But is it all, in the end, just self-serving and self-magnifying noise? Well, it depends. There is a place for the public confessional. I think of Brooke Shields’ book Down Came the Rain, where she talked about her own struggle with postpartum depression. I think of Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love, which chronicled her trials with recovering from divorce, lost love, and daring to love again. I think of Isabel Gillies’ It Happens Every Day, where she acknowledged her own responsibility in her ex-husband’s extramarital affair. And I think of Youngme Moon’s Difference, where she talked about the day she decided to stop teaching the way everyone else was teaching and how it changed her life and the lives of her students. These books fit the category of public confessional, and how glad am I these women confessed.

Their confessions have made me (and others, too, no doubt) feel less alone on this journey called life. And they have taught me new ways of thinking about and approaching my own existence. Knowing someone else has tried and failed and tried again…differently…gives me hope in moments when hope seems hard to come by.

Some of my friends and acquaintances will be surprised–those who think I limit myself to great, dead literary authors like William Faulkner, Thomas Hardy, Henry James, and Elizabeth Gaskell. But all these books, literary fiction and popular memoir, have something critical in common. Perhaps no one can set a scene like Thomas Hardy. And perhaps no one can jar our senses with “hit that nail on the head” meaning like Faulkner. But they are, in the end, all public confessionals–cutting open the writer’s view of the heart of life, whether achieved through fact or fiction. And these confessionals change us.

So let me confess….

I started this blog because I realized I had it too good in some ways.

Trained by experience to establish rapport with sources by finding that rock of shared experience that would make them trust me, I have been the recipient of more than a few confessionals over the years. And what I discovered from that and from the tools of journalism that I have transferred over to my relationships with friends and colleagues is that everyone has a story, many stories most likely, that they are dying to tell, need to tell. They are just waiting for the audience…the audience that often never comes. They want someone to walk into their lives who gives a damn, really, honestly gives a damn. Because life is hard, and life is scary, and isolation is the surest path to eternal torment.

I have received confessionals on a scale far deeper than any Catholic priest’s. And it has not, as you might imagine, given me a front row seat to the hidden melodrama of people’s lives. Rather, having that window into people’s souls has given me a window into my own. It has given me the courage to acknowledge my own failures, learn from them, and pass the lessons on.

The assistant instructor at the dance studio where I take lessons twice a week often remarks when teaching choreography she has just learned herself, “Let me act like I know what I’m doing here.” And we chuckle with some relief, glad perhaps to know that someone else is “winging it” besides ourselves.

I can recall having done the same as a young Humanities professor, teaching the history of early Western Culture, a subject well outside my area of expertise, a subject in which I struggled to stay a step ahead of my students. They thought I was the expert. How wrong they were. Yet I never let on that I had about as much expertise in the origins of Islam as the Walmart greeter.

But I grew up, as many of us do, with the idea that perfection is the goal. After all, the Bible (a centerpiece of western culture whether you are Christian or not) enjoins us to “be perfect as thy Father in heaven is perfect.” I don’t know if anyone else has noticed this, but this world we live in is far from perfect, and if you think God created it, then I guess you also have to figure He wasn’t perfect or that He was intentionally imperfect. So I think it’s probably perfectly okay and well within your rights if you are religious to perform imperfectly in this world. It might even be you were meant to do so.

That’s not an easy idea to get used to, however. Some of my most well-educated and seemingly level-headed friends still strive for perfection, still attempt to hide imperfection even from the people they love most in the world. How many times have you watched yourself go through the motions of cheerfulness when you did not truly feel it? How many times have you told your boss you can handle that project, no problem, when on the inside you’re terrified that you have no idea what you’re doing?

We all lie to each other…and sometimes to ourselves for the sake of civility. But where does civility stop and honesty begin? It is a difficult question.

I have a lifetime of experience in “acting like I know what I’m doing here.” I write articles that people trust to be accurate and true even when I myself am sleep deprived and pulling through with the aid of caffeine alone. I write columns that are supposed to inspire people to get off their rears and do something with their lives even when I haven’t the slightest idea what I’m doing with mine half the time. A friend of mine remarked to me not long after I’d returned from three consecutive trips that had me zooming through seven different time zones in the course of a month, “I wish I could live your life for a day.”

Really?

Perhaps it looks grand from where she is sitting. From where I am sitting, it often looks downright ridiculous.

There was a time, not too terribly long ago, when I felt some not entirely sane obligation to offer the appearance at least of the perfect life. I thought that, by virtue of the fact I had followed a childhood dream to fruition, it was my duty to inspire others to do the same—to make it look rewarding and wonderful to follow one’s heart. And it is. But not all the time. Not by a long stretch. Sometimes I feel like I am hanging onto my dreams with a tiny piece of thread that is slowly fraying.

We all feel that way, of course, at one time or another. But rarely will you find a person willing to admit it, unless you are interviewing her for an article on overcoming doubt. Most of us, for the most part, still hide behind our carefully constructed and often ridiculously transparent veils of perfection.

An acquaintance of mine said this is necessary, that we cannot bare our souls to the world. What an awkward place it would be. He has a point. You know those people on Facebook who announce to the world when they’re having a nervous breakdown? Yep, that’s a little creepy, I have to acknowledge. I’ve “unfriended” a few of those. It can be uncomfortable, at times, to have a front row seat to imperfection.

But maybe that’s only because we are not used to it. My jury is still out on that.

And though I’ve never given much heed to New Year’s resolutions, I might give it a go this year. My new purpose in life will be to be an inspiration, not by being perfect, but by being human…and being very good at it.

Posted by Deborah Huso on Nov 24, 2011 in

Motherhood,

Musings

Old Town in Dubrovnik, Croatia

“Good for me, bad for them.” These were the words my friend and student Zehra, a 40-year-old mother of three, spoke to me as we sat together in her cramped apartment in Newport News, Virginia, 14 years ago and watched the words “Crisis in Kosovo” flash across the television screen.

It was a memory I thought was long forgotten until my European travels took me to the Dalmatian Coast of the former Yugoslavia where Zehra once lived a couple of days ago. Once the scene of ethnic cleansing on a scale not seen since the era of the Khmer Rouge, the multiple nation states carved out of the country Tito once held together by force has few signs of the conflicts that dominated news screens through much of the 1990s.

The otherworldly scene I watched that day flickering on the screen of Zehra’s television of Kosovars fleeing their homeland in overcrowded trains or cluttered into muddy fields without food or shelter was not unfamiliar to Zehra, a native of Bosnia-Herzegovina, who, through some act of fate I’ve yet to understand, became my English student – my most dedicated one, I might add.

As part of my graduate school training in teaching English as a second language, I was required to tutor someone. Having followed the conflict in the Balkans since I was a high school student and then again as a college student when my boyfriend served aboard a carrier in the Adriatic Sea, I chose to tutor a family of Bosnian refugees.

It was supposed to be a two-month endeavor. Somehow the experience moved beyond grad school project, and I became the Sulejmanovics’ private tutor and only American friend for nearly four years.

English is one of the world’s most complicated languages, and teaching concepts like silent “e’s” and diphthongs to a family whose native Serbo-Croatian language is entirely phonetic represented an unusual challenge. And often, the confusing, inaccurate Bosnian-English dictionary I relied on when nothing else seemed to work only compounded my difficulties.

But the Sulejmanovics were more patient with me than I was with them. They laughed at themselves and at me when I tried to repeat the Bosnian words they attempted with little success to teach me. They showered me every visit with huge meals and introduced me to cheese burek and Bosnian style baklava. Always Zehra cooked in the style of the old country, keeping a 25-pound bag of flour in her kitchen pantry.

Their generosity to me was boundless, even when they had so little

For Zehra, seeing the Kosovars on TV that evening made her relive a nightmare past that I could neither begin to comprehend nor successfully console.

“It’s just the same,” she said to me, watching the terror-stricken faces of mothers with crying children. “The same.”

Zehra curled her arms to her breast and then with quivering lips described to me how Serbian police forced her family to abandon their home in Srebrenica, how she walked over the mountains in the snow with her youngest son in her arms.

“Mirsad,” she said, referring to her now pre-school age boy, “was only nine months old,” She began to cry. “Nine months old!”

She remembered bombs falling day and night, and her middle son Nedzad told me about the Serbian tanks rolling into town.

After leaving Srebrenica, the family lived in Tuzla for a time in a house with 25 other refugees, sharing one room with four other family members.

Understandably, she called her two-bedroom apartment in Newport News “big.” Many of her neighbors down the dingy apartment hallway were refugees also. Some were Serbs, and she felt no malice for them. One was her dearest friend.

As is so often the case in war, those most injured by it have the least interest or investment in it.

When I last saw her, Zehra was working in a camera factory alongside her husband, Sevad, a former teacher with an astounding grasp of geography. When Sevad, who felt out of place in theses strange surroundings where everyone seems to have money and where women are often as powerful as men, talked once of going home to Bosnia, Zehra clutched Mirsad to her and said she would stay in the United States, no matter what.

And she looked at me with soft brown eyes and then planted a kiss on Mirsad’s head – the baby she thought would never survive to attend American kindergarten.

Her gratitude to the twist of fate or act of God that brought her here was boundless, as was her devotion to those who helped her.

When I attended a parent-teacher conference with Zehra one evening and sat beside her as the teacher gave us glowing reports of Mirsad’s progress, Zehra looked at me, squeezed my knee, and said quietly, “My teacher.”

Weeks later, as she practiced the conjugation of English verbs with me, she said again with that affectionate and unforgettable smile, “I love my teacher.”

When Zehra came to the United States, she had only an eighth-grade education, could not speak a word of English, and had no employment skills. After four years of tutoring from her imperfect private teacher, she was outstripping her more educated husband in her understanding and speaking of the English language and her confidence in the new American landscape.

Until this week, Bosnia-Herzegovina seemed very far away to me, having long been absent from American television screens. It had dissipated from the radar the way war, conflict, and misery always do. Whether or not the lessons (if there were indeed any) from the wars in the Balkans stick remains to be seen. Prejudice, like family heirlooms, can be passed from generation to generation.

But not for Zehra. If indeed she had any prejudices against neighbors of differing faiths and ethnicities in Bosnia, they fell away when she landed on American soil. With survival often comes wisdom.

That Zehra came to smile again and think of mundane things like what to buy at the grocery store and what color to dye her hair taught me something I will never forget – that while there may be some things on this earth worth dying for, there are far more for which to live.

Posted by Deborah Huso on Nov 6, 2011 in

Musings,

Success Guide My husband said to me recently, after a disagreement about how I operate my professional and personal life, “You know I really admire the way you fling yourself blindly into life. It’s one of the reasons I fell in love with you. But it’s just not smart.”

You’ve probably heard statements like this dozens of times: “I love you, but….” We all hear them. They are the bane of happy relationships. If you love somebody, but this or that, maybe you shouldn’t be with him or her…unless, of course, you have to be. You have to look after your kids, your parents, that dog you adopted from the SPCA.

This post isn’t about loving some but not all of a person, however. It’s about living, not blindly, but, as I prefer to argue, openly.

And I’m not talking about hopping out of the proverbial closet if you’re gay or letting your grown children know you’ve divorced…six months after it has happened. I’m talking about being open to life, to the opportunities it offers at every turn, the opportunities we often miss because we’re afraid, afraid of trying something new, striking up a conversation with a stranger, saying “yes” when our self-protective instinct wants to say “no.”

Everything extraordinary that has ever happened in my life has happened because I took a massive leap of faith, defied the naysayers, hoped, believed, and closed my eyes and jumped. When I told an acquaintance of mine once that much as I enjoyed sea kayaking, I didn’t know if I was up for whitewater, he said, “Whitewater kayaking is all about fear management.”

So is life. Conquer your fear, and the thing you thought you couldn’t do becomes possible, manageable, maybe even smart.

For those of you who have been reading my columns in newspapers and magazines for the past decade, you have heard all of this, to some degree or another, many times before. But I think it bears repeating. It is probably why my dad, from the time I was a teenager until deep into my adult life, would tell me every time I left home to go on a date, return to college, go back to my apartment in the city, “Drive fast, and take chances.” He wasn’t talking about how to drive my car (though I’ve been lead-footed, I’ll admit, since age 16); he was talking about how to live my life.

Overcome fear. No matter what. Overcome it.

As many a philosopher has pointed out over the centuries, it is beyond fear that we find the true meaning of our lives.

When I was a child, I was incredibly afraid. Everything from piano recitals to going away for a weeklong church summer camp terrified me. They pushed me outside my comfort zone. It was one thing to play the piano in my parents’ living room, quite another to play it in front of an auditorium full of people. And it was one thing to have a sleepover at a best friend’s house, but to bunk in a cabin in the woods with girls I hardly knew? Now that was scary.

But as I grew older, I slowly began testing my own limits, learned to say “yes” to crazy, nerve-wracking things like singing the “Star Spangled Banner” at the opening of every high school basketball game and leading discussions on comparative religion in the college Humanities classes I started teaching at age 23, finding myself, on many occasions, younger than my students.

These small dares led to ever bigger ones because I had begun to discover that saying “yes” to things that terrified me taught me, little by little, to push through fear. And the amazing thing about fear is that once you push through it, it disappears. You’re not only never afraid of that particular thing again, you find yourself a little less afraid of the next scary thing because you’ve proved, after all, you can handle fear.

By the time I was in my mid-twenties, my fear management had grown to a whole new level. I was willing to drop a full-time, good-paying job at an ad agency, give up my penthouse apartment, and take a wild risk becoming a freelance writer in the isolated mountain reaches of western Virginia. Everyone, except my dad, told me I had lost my mind, and even my dad admitted, years later, that he thought I had lost my mind, too, but was smart enough to keep his mouth shut.

A lot of people will chastise themselves, when they are young anyway, for taking a risk and falling flat on their faces. After all, it’s pretty darn embarrassing when a girl turns down your request for a dance, so why on earth would you ever risk yourself by asking a woman to marry you? You see how this reasoning against risk-taking can get out of hand. Pretty soon, you’ll be avoiding everything that makes life worth living.

Consider instead, if you’re feeling a little fearful, of twisting your thinking. Learn to regret the risk not taken, and pretty soon it will become habit to put yourself out there. So strong a habit, in fact, that you’ll kick yourself until you’re black and blue every time you fail to take an opportunity and see where it leads.

I’m still beating up on myself for failing to get the business card of a Belgian businessman I met on an airplane a couple of weeks ago who sought me out because he wanted to talk to an American who could speak French. I was afraid he might think I was hitting on him. When I told my husband about this failure on my part later, he said, ironically enough, after I had described the gentleman, “I bet he’s in the diamond trade. You could have had a new client. You’re an idiot.”

Hmmm. I thought so, too.

I should have just flung myself blindly into the possible opportunity. But then, I don’t really see staying open to possibilities as a blind leap of faith. Rather, it is a calculated sense of foresight. Life is too short for giving into fear. Sure, you might embarrass yourself, offend someone, maybe even lose your shirt (metaphorically speaking). But that’s the beauty of risk…and of life. You really, truly never know what’s around that next corner. And if you operate from a place of opportunity instead of a place of fear, chances are whatever is around the bend is pretty darn grand.

Posted by Deborah Huso on Oct 23, 2011 in

Musings,

Success Guide The following essay was originally published in the March/April 2011 issue of Cooperative Living magazine.

Spring comes late to my home in Virginia’s Blue Grass Valley, this otherworldly place of high-elevation pastures and undulating ridgelines, with winter often extending into April. But when that last bit of snow slips down through the soil to rejoin the limestone earth and the whole valley flames fresh green from the swales of the creek beds to the tops of the sugar maples that crown Lantz and Monterey mountains, it seems no great thing to have waded through six months of winter if this rebirth is the reward.

View from the author's Blue Grass Valley farm

We humans are not so unlike the landscape that surrounds us. Like yellow jonquils and redheaded tulips that press forth through thaw-softened earth after their annual slumber, we sometimes lie dormant as winter for years until the opportunity comes for us to throw off the mantle of our former selves and transform into something akin to spring. Like the grass beneath our feet, we find ourselves changing and expanding with the seasons of our lives, often imperceptibly but occasionally with great force like the reinvented course of a mountain stream after a flood.

Last May, as Highland County was bursting into bloom, I crossed the ocean to revisit the land of my not-so-long-ago ancestors, those who had come here only a century before, to carve a life out of the black soil of the American Midwest, daring to leave life as the children of Norwegian cotters for the prospect of becoming landowner farmers in a landscape far different from the sidelong pastures of the Tresfjord where they were born with the smell of the sea always peppering the breeze.

Standing in the churchyard in western Norway where my great-great-grandfather was baptized, reading the family names across the gravestones — Naerem, Sylte, and Knutson — was to me a vivid reminder of the transformation my ancestors undertook all those years ago, hoping that by transitioning from one landscape to another, from the hardscrabble slopes of the Norwegian fjords to the thick black soil of the American prairie, they would transform their destinies.

And so they did, making a way for themselves, and for those of us who would follow, in a world without abject poverty, without the press of landlords, without the hardship of carving a living out of mountainsides more rock than soil.

When I came home again, America looked different, transformed. But it was I who had changed. I had witnessed the power of place in changing destiny. I had seen firsthand how impossible it would have been for me to be who I am or do what I have done had my great-great-grandparents not been brave enough to change their lives forever. And I began to comprehend at last what my college mentor had meant all those years ago when he talked of “the right to rise,” our American birthright.

He, too, knew the transformative power of leaving one landscape to join another, having come of age in a ghetto in Nazi-occupied Budapest as a Hungarian Jew. It was his father who enjoined him after the Communists came to power to risk a border crossing and find his way to America. And so he did, landing in New York City with $1 in his pocket. He read the speeches and writings of Abraham Lincoln to teach himself English and is today, more than half a century later, one of the world’s foremost Lincoln scholars.

I do not know, given his hopes I would become a historian, too, if he would understand my less-dramatic change of setting — why I emptied all my savings almost a decade ago to purchase a house and land in Highland County with no immediate prospect of employment, only the hope that I could do as I had long dreamed of doing, to make my way in the world as a writer in a landscape I had loved since childhood. Certainly no one else in my life understood.

But I had already learned, by that point in my life, that change, transformation, rebirth, do not come without risk, and rarely do they come without suffering. And when, at age 26, I came to Highland with the first carload of my life packed in boxes to find my driveway flooded by the snowmelt of early spring, the creek overflowing its banks, and coursing a foot or more over the dry ford, I laughed, rolled up my pants legs, and proceeded to carry my life, box by box, across that stream to my new home, the first of many challenges that would face me in the years to come.

And since that spring almost a decade ago, I have found my life transformed many times, frequently by landscapes, sometimes by people, and occasionally by pain. All the world’s major religions refer to these journeys of transformation and rebirth, how they are little removed from the journeys of the grass and trees that die back each winter to be reborn again in spring. But if you are not in tune to these cycles, as the farmer is to the character of the soil, it is easy enough to miss the opportunities they provide. It is not every seed that finds its way through the topsoil to become a walnut tree.

Did my great-great-grandfather know when he boarded that ship in Molde, Norway, that he was changing the course of history for all his progeny? Did Gabor Boritt know when he ran across the heavily guarded Hungarian border into Austria that he would one day receive the National Humanities Medal from an American President? Do any of us know when the chance comes to change where that change will lead?

We do not, of course. And sometimes we do not even recognize the chance, or we fail to embrace it out of fear, forgetting this is the natural cycle of things — change and rebirth, like the re-greening of the landscape in spring. But imagine if the snowdrops and crocuses failed to break through those last patches of snow, if the maples did not uncurl their new springtime leaves, if the pear and crabapple blossoms did not spray the hillsides in white and pink. Each year they return, a little more brilliant than the year before.

And so must we, remembering always how like brown grass and winter tree limbs we would be if we did not have the courage to embrace our own opportunities for renewal, whether those transformations come through the power of place, through love lost or gained, through pain overcome, or through the simple daring to be fully present in this — the lovely landscape of our own human lives.

Posted by Deborah Huso on May 22, 2009 in

Musings

Travel writer Deborah R. Huso

For better or worse (and often it’s for worse), most people believe what they read, especially if it’s in a book, magazine, or newspaper. If it’s on the front page of a major U.S. newspaper, it must be true, right? Well, journalists are kind of like attorneys.

More often than not, it’s our job to negotiate the truth.

Does that mean we lie? Well, not really, though we occasionally do omit…. As a longtime travel writer, omission has been a particular friend of mine. No glossy travel magazine wants to publish an article about a weekend beach rental where an innocent man (my husband) was attacked by fire ants or about the front desk clerk at an art museum who sent the security staff after a supposedly dangerous yet completely innocent patron (me).

Because publications don’t want to scare their readers away from the very thing they’re trying to sell–travel–or offend the purveyors who are advertising in their pages, sometimes the real story (or at least some of the best and worst parts) gets glossed over, only subtly recorded, or, most commonly, left out.

The result is that I have a horde of truly incredible experiences that have never made it to print and likely never will. Sometimes I feel my readers are being misled into believing it’s perfectly enjoyable to walk around the Mayan ruins at Tulum when its 101 degrees outside or that you’ll never be seated at dinner on a cruise ship next to a couple from Kentucky who still use the term “colored” when referring to human beings who live down the street from them. At the same time, they are also missing out on the utterly ridiculous experiences that make vacations so memorable.

So I decided it was high time the rest of my travel stories made it into print…and video…even if only on the web. Stay tuned. Your access to the band leader of a group of marching pink flamingoes and some upside-down flute players dangling from a 100-ft. pole will soon be but a click away….

Deborah

P.S. If you’d rather stick to the conventional stuff, however, you can visit my web site at www.drhuso.com. Happy travels!