Posted by Deborah Huso on Feb 16, 2017 in

Musings,

Relationships,

Success Guide “If you’re really a mean person, you’re going to come back as a fly and eat poop.” –Kurt Cobain

You don’t have to be a Buddhist to respect and appreciate the law of karma. It’s kind of like confronting an armed man in a dark alley and saying, “No, I’m not going to give you my wallet in exchange for my life.” Reasonable people just don’t mess with that shit.

Unfortunately, it appears there are more than a few less than reasonable sorts out there who are willing to sacrifice their lives (or at least the quality of their lives) for the sake of hanging onto that wallet.

History and popular culture are filled with folks who didn’t believe the karma bus would ever come calling—think Kenneth Lay or Jeffrey Skilling. Or larger karmic outcomes like the rise of ISIS in the wake of Western powers abandoning wars they initiated and leaving shaky and corrupt “democratic” governments to handle the fallout.

Karma is basically the philosophical cousin to Newton’s third law of physics, which states that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Be a distant, critical, and unloving parent–be prepared for your children to hate you and abandon you in old age. Treat your co-workers with repeated disdain and backstabbing–don’t expect anyone to come to your defense when lay-offs start.

But here’s the thing about karma: It can be slow, and it’s not always obvious. Which might just be why so many people think they can escape its clutches and why so many of the rest of us rail against the karma bus’s failure to arrive at what we feel is its designated stop.

The Dalai Lama advises, “When you have made a mistake, take immediate steps to correct it.” The idea here is that you can fend off bad karma from a bad action by making things right again. But don’t suppose you can make things right by working in a soup kitchen after cheating on your spouse or donating money to a charitable cause after blindsiding your business partner. “Non sequitur,” as we journalists like to say.

In other words, you’re still going to hell…or at least purgatory.

You’re still going to die alone of terminal cancer with no friends or family who really care all that much because you’ve alienated them all, failed to nurture your relationships, or maybe never chose real relationships to begin with.

And maybe all the people you hurt, abandoned, or took advantage of are dead or senile by then, and maybe you’re senile, too, but who wants his legacy to be heart attack after indictment for a massive Ponzi scheme or slow death among indifferent strangers who have to be paid to change your diapers?

I had a great aunt who died in her mid-90s after many years as a widow. While some of her age and generation wailed about grandchildren who didn’t visit them, she was taking pictures with a digital camera at her great-granddaughter’s volleyball games, chatting via email with her children, and reserving vacations with other adventurous strangers on long bus trips to national parks.

“Happiness is not something ready-made,” the Dalai Lama tells us. “It comes from your own actions.” My great aunt probably didn’t think much about karma, but she lived as if she did….

So how do you ensure you’re not sitting on a stinky cow eating poop in your next life? Or maybe even in this one?

Here are some tips….

- Stop fulfilling your own negative prophecies. Let go of the past. It’s only an informer of the future if you let it be.

- Do something different. So you think life is meaningless and sad? It’s probably because your existence is like the movie Groundhog Day. Go for a hike. Take a class. Ask someone in the grocery store line out for coffee.

- Build real relationships, and then nurture them. Love people for who they are, not what they can do for you.

- Dump toxic hangers-on. If your friends only come calling when they need something and frequently fail to show up for you unless you’re buying the drinks, shed them. No friends left after that? Refer to no. 3….

- Practice gratitude. Be thankful for the good things in your life. And remember to thank the good people who look out for you.

- Be vulnerable. Smile at strangers. Tell a friend your most secret fear. Admit it when you’re in error.

- Stop taking offense. Try not honking and cursing at the driver who cut you off in traffic for starters. And if you feel criticized by a friend, look for the loving intention before you lose your temper.

- Say I’m sorry, and then prove it. Not by working in a soup kitchen but by working on yourself.

- Be honorable. Speak the truth, especially about yourself. And do the right thing, especially for others.

- Say “I love you” daily, even if it’s to your cat, even if it’s to yourself.

And as for all those folks who are angry, bitter, and mean…well, walk away, trust the karma bus, and let them eat poop….

Posted by Deborah Huso on Sep 18, 2016 in

Musings,

Success Guide My maternal grandmother was born in 1922. A Midwestern farm girl, she lived through the Great Depression and World War II. She was part of that revered group known as “the greatest generation.” She married at 18, had my mother two years later, then my uncle.

She could whip together a massive and tasty meal for a group of farmhands while my curly-haired uncle sat nearby in his highchair and my mother clung to her leg. She baked bread while her family slept, could drive a tractor, worked in a lawnmower factory many years alongside her husband, then came home in the evenings to work the farm, trying to pull together the money to send their two children to college—quite the dream for a woman who was the first in her Norwegian-American family to graduate high school.

She took life by the horns, but, in “greatest generation” fashion, she did it with grace. Too poor to buy suits from a department store, she made her own clothes, modeling her Sunday attire on the suits she saw Jackie Kennedy wearing on TV. She paired them with white gloves, high heels, and pillbox hats set atop her dark red curls. She had steely blue eyes, but she rarely smiled—she was ashamed of her less than perfect teeth.

My dad (her son-in-law) remembers her as a force to be reckoned with—one who would turn heads the moment she entered the high school theater to watch her daughter in a play. Never mind that she worked hard and had rough hands. She radiated an aura of dignity and strength.

She wore high heels to church on Sunday until she was nearly 90. She put on pretty blouses, jewelry, and lipstick to go to the grocery store.

She was… is…my model of what a woman should be—resilient, courageous, and willing to do what needs to be done.

Her husband, my grandfather, like her, was not perfect. But he aspired to great things; he was ambitious and entrepreneurial. Some said he had the best farmland in Cottonwood County, Minnesota, and he worked hard, played hard, was as stubborn as he was small and skinny. He was a voracious reader—in the attic of my grandparent’s house are boxes and boxes of his books, mostly history. Saturdays would find him playing baseball—lanky and quick, he could run like the wind. He lived on strong coffee and Lucky Strikes, adored his four granddaughters, wanted them all to have red hair just like his wife, paid off his farm before he died—young, at age 63.

Seven miles north of my maternal grandparents’ farm, my dad’s parents lived. My paternal grandfather, only a second generation American, was president of the local bank and a member of the schoolboard. He wore suits to work every day, accompanied by a fashionable hat, which he removed whenever he entered a building. He was distant but carried within him a deep desire to do good, to change his little corner of the world. When local farmers couldn’t qualify for loans at the bank he oversaw, he provided them “character” loans out of his own pocket.

These were the potent models of my youth—their strength of character emblazoned on my memory….

I remember reading a book in college by Michael C. C. Adams, The Best War Ever, in which, to a degree, he debunked the American myth of World War II as a time of prosperity, equality, and national unity. But he couldn’t debunk the greatest generation. There was no undoing the fact that the cultural norm (or at least aspiration) of that period included a phenomenal sense of doing the right thing (even if history would prove it wasn’t always right), being a man (or woman) of character, eschewing the self-absorption so common to our modern world, and giving one’s all.

I was at a conference this last week in Berkeley, California, where life is a bit more lax than in the East. In my typical nod to the manner of conduct my grandmother taught me, I dressed in a suit and heels. Always, she advised me, one’s dress should reflect how one feels about what one is doing or whom one is with. (Perhaps I owe to her my discontent with a man who wears flip-flops and shorts to dinner.)

Let’s just say I was severely outnumbered by much more careless attire at this Pacific Coast event, and one of the conference attendees even came over to me and said, a bit snippily, “So I guess you are one of those women who can do everything and can do it in heels!”

A little miffed, I replied, “Well, yes, this is how I roll.”

And, to a large degree it is. Because I can’t really get the “greatest generation” out of my soul. Or maybe it’s ancestor guilt—being the great-granddaughter of Scandinavian immigrants who came to the U.S. with little but were soon landowners, had banker sons, doctor grandchildren.

Be better.

Lift the next generation a little higher.

Recognize your individual responsibility. Don’t blame others for your failures.

Be honest about who you are and what you stand for.

Know how to take care of yourself and your family.

Don’t be pitiful. Don’t whine.

Care about the welfare of your friends and neighbors.

Do good.

Don’t pretend. Actually be the person you envision in your soul.

I won’t claim my grandparents were infallible. By today’s standards, many of the greatest generation’s cultural norms would be considered downright dysfunctional—like staying in an abusive marriage, hiding one’s pain from family and friends, maintaining stoicism (and stubbornness) in the face of trouble or the revelation of personal fault.

I am a student of history, and I look at my grandparents’ generation through the lens of history, through the cultural standards of their time.

My maternal grandmother met my grandfather at a dance. Those were the days when, unless you were Baptist, knowing how to dance was a social requirement. I am sure she danced backwards beautifully in heels. Because that was just how she rolled….

Finding women and men of that ilk today is no small feat, and grace is a largely lost art. Grace of conduct, grace of soul.

Back to Berkeley: When I sidled up to the bar at the hotel where I was staying, I was soon joined by a man to my left, who asked, “Is this seat taken?”

“No,” I replied. “Help yourself.”

Given his camaraderie with the bar and restaurant staff, I knew he must be a local and began asking him about the restaurant scene. He obliged, all the while wearing a baseball cap…indoors…when it would have taken half a second to remove it.

These are the things my grandparents taught me to notice, and my mother contends it has all made me a very fussy woman who is overly selective in her intimate friends and romantic interests.

Perhaps.

But, if the greatest generation has taught me anything, it has taught me to hold myself (as well as others) to high standards and to aspire to and inspire in others a striving toward what the Buddhists call Nirvana but which is merely learning to feel divinity and exercise grace regardless of one’s outside circumstances.

I prefer to call it skill in dancing backwards in high heels.

Posted by Deborah Huso on May 17, 2016 in

Musings,

Relationships,

Success Guide “No one saves us but ourselves. No one can and no one may. We ourselves must walk the path.”

― Gautama Buddha

It’s a primal fear—being alone.

There are good reasons for this. Belonging means survival. Not just in nature. Even in civilized life. It’s such a deep, primal fear that many of us choose being miserable in a group, in a relationship, in a family, merely to avoid that dark chasm known as being alone.

There are good reasons for this. Belonging means survival. Not just in nature. Even in civilized life. It’s such a deep, primal fear that many of us choose being miserable in a group, in a relationship, in a family, merely to avoid that dark chasm known as being alone.

But is it really so bad?

Some might argue I come to this “alone” business from a decidedly prejudiced angle. After all, I grew up an only child in a rural community 30 miles away from my closest friend. It wasn’t like I could run down the street to find someone with whom to play. My parents both worked, often long hours. I learned, from very young, to be comfortable spending time unto myself. As I grew older, there were plenty of times I preferred it even. After all, a 24-year-old single woman does not move to the least populated and most isolated county in Virginia because she is fond of lots of regular company.

But here’s the thing: I actually didn’t learn to be alone until quite recently.

Because learning to be alone isn’t about being able to pay the bills all by yourself, taking care of a household, a farm, a child, whatever it is one has to do in life…all by yourself. No….

It’s about being enough, as you are, where you are, whether you’re with someone or not.

And frankly, most of us are not very good at this.

Sometimes we say it’s because we just don’t have time to be alone with ourselves. That requires some self-knowledge and some self-nurturing, you know. And I get it. There have been times in my life where the most self-nurturing I could muster was locking the bathroom door, so a toddler and a dog wouldn’t stand there staring at me as I sat on the commode. And the most self-knowledge I had was doing something stupid, like walking down the aisle, with the knowledge it was stupid…but doing it anyway.

And when you fail to know yourself and nurture yourself, strangely, you have a tendency to want others to fill the gap, the void, the big empty room in your mind.

The result of that you have likely witnessed if not experienced yourself:

The couple that marries, well, because everyone else is doing it, and they don’t want to be left out.

The guy that tries to start a relationship with a new girlfriend before he ends the one with the girlfriend he’s got because he’s scared of that empty space of “having no one.”

The woman who stays in a miserable marriage because she’s scared she can’t handle life “alone.”

The person who hangs out with people she’s really not all that fond of or doesn’t relate to just because it’s less scary than sitting at home by herself on a Saturday night.

The man who spends every evening glued to the television or maybe the iPad because he doesn’t really feel connected to his wife but can’t bear sitting alone with his “loneliness.”

The woman who hops from one relationship to the next, failure after failure, because the idea of being alone terrifies her, even though she knows (perhaps) that being alone might just stop the painful cycle….

I exercise no judgment on the above. Who has not done these things or things very like them?

Heck, it wasn’t so long ago that I was dating, ultimately (when I really decided to think about it), because it seemed like a divorced, relatively young, intelligent, not terribly bad-looking woman should be dating, not sitting home alone.

And then one day it just kind of hit me that dating was mentally exhausting me, not enriching me. I’d cringe when I’d hear the bleep of a text or the ringing of my cell phone. I’d respond out of obligation, not desire. I’d sit across a dinner table smiling brightly because I was polite and gracious, not because I was actually happy to be there. I’d wince at the thought of another kiss from a middle-aged man who ought to be better at this stuff after three or four supposed decades of practice….

I found myself longing for my girl and guy friends, my daughter, a quiet night alone with a book and a glass of wine or cup of tea. I craved the nurturance of the people who already knew and loved me, not strangers. And sometimes, I just craved taking a nap alone in the sunshine.

I discovered I was enough, that my life was enough, that those I already loved were enough, and that everything was full, and rich, and good, whether I was sitting home alone in front of the fire, cloud watching with my daughter on a picnic blanket, or pulled up to a dinner table with my most intimate friends.

Likely, at some point in your life, you have heard a friend or acquaintance say something like “It was only once I became comfortable with being alone that I met the love of my life.” This is not some hokey adage that says love will only come to you when you stop looking. No. It’s really about being comfortable in your own skin and, by extension, enabling others to feel comfortable in theirs.

That is the careful art of being alone. When you relish your own company and generate your own joy, others will not only be drawn to your seemingly easy bliss, they may even begin to emulate it.

Posted by Deborah Huso on Mar 22, 2016 in

Musings,

Success Guide,

Travel Archives “Life begins at the end of your comfort zone.” –Neale Donald Walsch

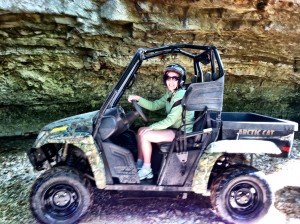

The weekend I learned archery AND how not to fall out of an ATV while driving sideways down a creekbed.

There was a time when piano recitals were one of the most dreaded things in my life.

I hated them, hated everything about them. First of all, preparation for them involved learning the most difficult composition of the year—some piece of classical music designed to show off all I had learned through 50-some weeks of lessons. And it was rarely a song I enjoyed playing…in no small part because I didn’t enjoy playing things that didn’t come easily.

Kind of the way I didn’t like Calculus. Or physics. Or football.

None of it came easily, you see.

And my parents, teachers, and coaches were so good at noticing all the things I did well that they really didn’t worry themselves about the areas where I struggled and then, usually, quit. Like piano. My mom said if I really hated piano lessons, I could stop when I turned 13, and I did.

In retrospect, it was one of a host of stupid decisions I made in my life out of laziness, boredom, self-consciousness, and an unwillingness to expose myself to the possibility of failure. Today I sit down at my piano and stare longingly at sheet music I wish I had the depth of skill to play.

Looking back, I can easily say I have lived more than half my life in fear.

Fear of how stupid I might look in trying something new.

Fear of being judged.

Fear of being ridiculed.

Fear of not being understood.

Fear of suffering.

Fear of being alone.

Fear of being abandoned.

Fear of not being smart enough, strong enough, good enough….

Fear of being KNOWN.

I couldn’t tell you when I finally snapped out of this. I don’t believe it happened in an instant. It was a process, a long and sometimes painful one.

I just know I was hiking one of the steepest trails I’d ever hiked (yes, this was before the Grand Canyon) with a friend and his son, the uber fit youngster looking like he was out for a Sunday stroll while outpacing us by several hundred yards. My friend turned to me and asked if I needed to rest.

“Nope,” I replied, though the sweat was pouring down my temples, “I’m good.”

And he grinned a little at me and said, “You know, you’re a really good sport. You’ll do just about anything, and you don’t complain about it either.”

I’m sure I looked at him a little sideways. I’d certainly never thought of myself as a good sport even though it’s one of those phrases parents bandy about, perhaps out of some obligation they feel to at least attempt to instill values of adventurousness, courage, and comfort with struggle or failure in their children.

But when I thought about it, my friend was right. Somewhere along the way, I had indeed become a good sport. And more than that, I’d gotten pretty fearless.

Mountain bike racer Jon Brickner: In all fairness to myself, do you see how tiny and wiry this guy is??

Sitting in a front row pew at church, anxiously waiting my turn to race through my dreaded recital piece on a clunky church piano as quickly as possible, I’m pretty sure I never dreamed in a million years I’d have the chutzpah to go mountain biking with one of the nation’s top racers (and yeah, it almost killed me) or to sit on the ocean floor, removing and replacing my dive mask at 60 ft. below the surface without launching into a full panic (and yes, I laid awake the entire previous night with anxiety about it).

I also never imagined I could love so deeply and be battered so wickedly and have the guts to go in for another round, and another. Or that I would be the kind of person who could pick up stakes and move every couple years, switch jobs every few months, and then finally throw up my hands and go out on my own without the slightest idea if I could really make it work. And I still haven’t proved if I can….

Somewhere along the way, I’d started trying to be like the famous Crazy Nastyass Honey Badger. I just did not give a shit.

Heck yeah, I sang a few lines of “Crazy” at the Ryman!

I did not care if friends or relatives thought I had lost my mind. I did not care if it was dangerous to walk the streets of South American cities alone. I did not care if a piranha might eat my arm off. I did not care if I toppled off my standup paddleboard into the freezing Tennessee River. I did not care if anyone else was watching me dance or hearing me sing. I was learning to push my own envelope and in the process learning that it was outside my comfort zone that real life begins.

While you’ve undoubtedly watched the viral honey badger YouTube video and snorted laughter, how deeply have you considered the honey badger’s philosophy on life? Yeah, I’m being serious. Don’t forget that National Geographic has called the critter “the most fearless animal on the planet.” It will do, chase, eat anything.

And while it’s doing all this wild living, scavenging birds and foxes follow it around, too lazy (suggests the narrator) to go fight for their own meals, waiting to get the leftovers from this badass rodent. “The honey badger does all the work while the other animals just pick up the scraps,” notes the narrator.

I start thinking about these scraps. And people I know who survive on them. Getting by. Marking time. Watching life from a safe distance. Going in only when they’re absolutely certain the coast is clear.

And, of course, when you wait too long, curry safety over experience and security over destiny, scraps are what you will get.

If you ever thought “being a good sport” was about “settling,” reconsider. It’s really about getting out there, being willing to go for the biggest prize, and being able to feel good about yourself even when you don’t land it…because you know you tried, you know you lived, you know you pushed through fear.

What’s pushing through fear worth? Well, you certainly aren’t going to know until you’ve done it. But I will say the other side of fear is pretty euphoric…and worth giving a try.

A close girlfriend of mine once said to me, “You’re the bravest female friend I have who isn’t a lesbian.”

Well, she didn’t call me the “honey badger.” But close enough. I’ll take it.

Posted by Ben Weaver on Oct 19, 2015 in

Fatherhood,

Musings,

Success Guide There exists some conventional wisdom that the average person changes careers seven times over the course of his or her life. Though I doubt the veracity of the claim, it stews in my current state of mind, “Four more? Is that what the back 40 of my life is going to be like?” As I ponder my future prospects, I wonder if I even have it in me.

See, I was one of those people who thought he could do the one thing he did (in my case, teaching) until he was ready to retire on a modest pension with his house and student loans paid off. Fresh out of college and a year of AmeriCorps doing volunteer teaching, I was going into my first teaching job like most other liberal saps, sure that I was going to “make a difference.” Even after a couple of years of teaching in a decades-old trailer with mouse holes in the floor, walls, and ceiling in Orange County, Va., I was undeterred. Oh, those little fuckers were going to undergo some serious transformation under my watch! Like so many other young and idealistic morons, I was going to CHANGE THE WORLD.

Yeah, okay. After a decade or so of teaching mixed classes of special ed, I had few illusions left to shatter. Sometimes little Norman just wasn’t going to pass his standardized tests no matter how many times you tried to get him to compose a five-paragraph essay on the social impacts of our First Amendment freedoms, especially if he hasn’t developed a full grasp of the alphabet by the time he’s in 8th grade. If Walter hasn’t learned by 17 that it isn’t appropriate to masturbate under his desk, he’s probably going to be beating it in a cubicle until they fire him from increasingly low level jobs for the rest of his life.

I was at peace with that. No, not changing the world…but have you heard that little parable about the little girl throwing the starfish back in the ocean? It is dumb, and I hate it, but yes, sometimes you just need to make a difference to one to make it all seem worthwhile.

Somewhere around year number 13 into teaching, something went terribly wrong. Many, many teachers got laid off, and the special education staff was slashed almost in half. One summer, after six comfy, complacent years teaching 8th grade civics, I got called to the principal’s office and asked if I wanted to take over the school’s program for the emotionally disturbed.

Say, when you put it like that, it sounds like you’re moving up in the world! I just knew getting that ED designation in grad school would make me an attractive candidate for a management position! Then I found out that meant everyone else who was doing it quit, and I would be the only one teaching three grade levels of bat shit crazy, potentially volatile kids all in the same room and be responsible for all their casework plus four SOL subjects per grade level.

I laughed in that man’s face. “I’d rather work construction” were my exact words.

So that’s what I did, starting my own business doing home improvements. I really didn’t know shit, but I’m a quick study. I’ve often said I wouldn’t have gotten anywhere in life if not for a ready willingness to get in over my head. By and by, work and opportunity came my way, and I did my best to take advantage of it. By year number three, I had two regular employees and was subbing out lots of work. Things were great, and money was flowing but….

I was terrified. Shit, what if I lose this contract? (I did) What if I can’t pay the mortgage on the house? (thankfully never happened) What if the wife leaves, and I’m the only income? (she did, and I am) What if I accidentally shoot myself with a nail gun, and it lodges into the part of my brain that controls my ability to get erections? (somehow dodged that one) These are the things that keep men up at night and wear on their souls!

It all wasn’t without its merits, however. Having had a chip on my shoulder toward authority since gestation, I am well-suited to being my own boss. I don’t like taking other people’s shit or suffering their mistakes, and for the most part, I didn’t have to…with regard to work, at least. Want to take the day off to do paperwork and send the crew out to work? Want to have a beer with lunch? Want to be able to fire people who get on your nerves? Verily, I say, it is good to be the boss.

As much as I loved the freedom and self-satisfaction, when a job offer came my way with the promise of a big steady paycheck and the accompanying security for Henry and me, I jumped right on it. Daily travel? Oh, yeah, I love travel. Thirteen-hour work days? No problem, I hate sleep anyway!

In the heat of demonstrating that can-do, positive attitude and holding faith that things will work themselves out, one can easily look past the detriments of a life of hard labor on the road: maintaining a 50/50 custody arrangement is exceedingly difficult, as is maintaining relationships.

– Time to yourself? Good luck with that! You’ll feel guilty that you didn’t spend time with the friends you never see anymore.

– Want to see your kid at least once during the work week? You’ll hear about it because you can only work a 10-hour day in order to pick him up from preschool before it closes, never mind that you worked through lunch.

– Certainly don’t get caught up about knowing where you’ll be next week or the week after or trying to plan a life around work because it isn’t going to happen.

Not to say that I don’t enjoy certain aspects of life on the road. Visiting corners of the world I haven’t yet seen, finding holes in the wall serving up the local specialty, spending time outside through the beautiful Virginia seasons… all of these things are easy to find pleasure in. As well, like a Siberian husky, I need and crave the physical exhaustion that accompanies a long day of labor, when the persistence of thought abates and my mind can be empty. Some people do yoga; I prefer shoveling gravel and tossing 80-pound bags of concrete. I swear, it makes me a better person on so many levels.

But life on the road sucks when all you really want to do is be there for your kid as he grows up. I’m over leaving tears on the pillowcases in shitty hotel rooms at this point, but I do wonder how I’ll make it work in the long-term. I know I only have about eight more years until he hates my guts, then another five to eight before he figures I’m less worthy of contempt again, if I’m lucky. The knowledge that these days of endless hugs and unbridled enthusiasm will not last forever is unsettling… but, then again, so is the prospect of homelessness.

Every once in a while I’m put in a position to make a decision between security and the gambit of potential greatness versus utter failure. While I’ve certainly done things for the sake of security, none of them are story worthy. The times I have said “fuck it” have always been my defining moments, for better or for worse. While I still don’t know for sure what the resolution to my current situation will be, I remain certain of this much: a life without risk is a life unfulfilled.

Kayaking in the Tetons

Every once in awhile my “aloneness” in the world hits me. Okay, so I’ll be honest—it’s not every once in awhile; it’s pretty much every other day.

The last hit occurred when I was on assignment in the Grand Tetons, working my way through a three-day kayaking, rafting, and camping trip on Jackson Lake and then the Snake River. Joining me on this journey were two couples—one fairly young and recently wed, transplants to the west who had moved from Chicago; the other was a couple in their 70s from West Virginia who had shared a long and adventurous life together.

As we were unloading our camping gear that last night of the trip to set up camp on a desolate but beautiful peninsula beneath the gray shadow of Mt. Moran, I happened to notice the male half of the young couple carrying the bulk of his and his new bride’s gear up from the bouldered beach to a camp site at the edge of the woods. When he was finished, pitying me a little apparently, as I hoisted a heavy dry bag onto my back and then prepared to follow it with a sleeping pad on my head, he came to my aid without speaking, taking the heaviest items from me.

I was astounded. Most of the time, I can’t even entice a man to help me get a large suitcase out of the overhead compartment on an airplane even when wearing a wrist brace, trying to hang onto a small child, and obviously struggling. Yet this young man helped me without being asked and obviously with no expectation of the reward he might receive for carrying out such labor for his young wife.

Camping on Spaulding Bay

After thanking him profusely, I began to set up my tent for the evening. I wasn’t struggling really. The task was relatively easy, just a bit awkward for two hands as opposed to four. The 70-year-old gentlemen camped near me soon came over to help and even directed me as if I was a an untried Girl Scout, which was fine. It was rather sweet actually. When he was done, he returned to his own campsite to exchange relaxing foot rubs with his wife—a phenomenon rarely seen among newlyweds much less among partners who have lived together for decades.

Once my campsite was in order, I settled down to rest behind the tent, staring off into the now glass-smooth surface of the lake, granite mountains with glaciers tucked into their crevices facing me across Spaulding Bay.

And I began to feel the aching absence I have known so much of my life.

“What is it like to have someone carry your bags for you?”

My women friends are all married, the smallest handful happily, a few miserably, and most of them in a stalemate of resigned acceptance. So far as I have seen, however, their husbands all carry their bags. Some may groan and gripe over the task, but they do it, dutifully, sometimes robotically, but sure enough, the bags end up properly placed in the trunk, in the overhead compartment, locked safely away from bears in a steel box, whatever.

I watch from the sidelines, envious at times….

You see, I have rarely had a man carry my bags. Even when I was married, my husband was in the U.S. Navy and more away from me than near, so I lived the life of a single woman, seeing him on occasional weekends or sometimes not at all for months on end.

Wandering the Malecon in Guayaquil, Ecuador

I carried my own bags, mowed my own grass, fixed my own fence, and repaired my own plumbing. I flattened myself into narrow, dirty crawlspaces to troubleshoot furnace issues, test drove and purchased my own cars, carried heavy children in my arms through amusement parks, and found my way alone through foreign airports in strange cities.

I was (and am) the mistress of self-sufficiency…just as my parents intended me to be. All my life they prepared me for a cruel world where I should “trust no one.”

Under this hardline, Scandinavian tutelage, I grew into a woman who could pretty much do anything necessary to handle the basics (and the mishaps) of everyday living. I taught single girlfriends how to change rusty and clogged water filters, repaired my own crotchety lawn equipment, and figured out how to grease stubborn, tight windows so I could close and open them with ease.

I’ve had no need for a man in my life. I am my immensely practical builder father’s daughter….

This last week, however, my seven-year-old daughter has been working on a curious project at school involving trust and team building. I can recall, in school and college, how I dreaded group projects because I knew I would not only always be the lead, but I would also always be the one carrying the bulk of the workload. I trusted, generally with reason, no one.

But Heidi’s project encouraged these things called trust and teamwork. Her class spent a morning at her teacher’s farm, learning to trust one another—closing their eyes and falling off picnic tables with the solid belief classmates would catch them.

And I could not stifle the doubtful Midwesterner in me who wondered, “Should Heidi be learning this? Won’t it harm her in the long run to believe others will be there for her? Besides me, of course? Would it not be better to prepare her, as I have long tried, for solid self-sufficiency?”

For I have, perhaps even more doggedly than my parents before me, adopted a hard line with my daughter, refusing to carry her luggage in airports, encouraging her to find bravery within her soul, nurturing her fearlessness—all in preparation for the day when she will have no mommy to carry her bags, wipe her tears, hold her close in the dark hours of the night when the whole world seems stacked against her.

It is no cruelty on my part. It is an act of love.

I don’t want tears welling in her eyes when she watches a man carry his wife’s luggage, kiss away her tears, or hold her when tragedy strikes. I want her to know she can carry her own burdens and survive.

As I have carried mine…across two decades, across four continents.

Camping at the base of the Grand Canyon along Bright Angel Creek

People often ask me why I take these journeys—backcountry treks into the Tetons, the Grand Canyon, the Smokies. Less than prudent rambles through dicey South American cities, into dusty and hardscrabble Mexican towns, into sad shops populated more by stray dogs than people in Puerto Rico.

It is partly about character building but mostly about facing fear and uncertainty. Walking through it…alone…and knowing I can do it and come out the other side. And sure, life should be about more than survival and fear facing, but those are two things you must conquer first…before you can conquer anything else.

Would that I did not have to conquer these things alone.

But there is ample reason for why I carry my own bags. It is not just my upbringing. It is not just my independent nature. Part of it is an unwillingness to settle for just any Sherpa.

I want someone who will lie on his back in the woods and name the stars for me, who will race me in his kayak across Glacier Bay and laugh and paddle backwards as icebergs crash into water. Such men are few and far between…. Men of my age have been too burned by the demands of young and foolish women, and most have retreated into a safe sort of nothingness far removed from the rambling of Grizzly bears in the woods and the pressing crowds of St. Petersburg in summer.

They do not seek the land of the midnight sun.

So instead of settling, I carry my own bags, bear my own baggage, and venture into the wilds of life alone, choosing experience over safety, and hardship (at times) over comfort. Because this is life, lived only once, with or without love, with or without someone to carry my bags, with or without the safety of someone’s arms to collapse into in the darkest hours of the night…but never without living and never without the sometimes hard to summon courage that drives one steadily to an existence without the base ugliness of regret.

I may die holding the baggage of my life in two arthritic hands, but I will not die without knowing I have lived.

Posted by Claire Vath on Mar 11, 2015 in

Success Guide,

Writer Rants Once upon a time, my vision of becoming a writer involved jetting off to white sugar beaches and surveying the Paris skyline from the vantage point of the Eiffel Tower. Then I became an editor at a farm magazine. While I spent a good portion of my career there tanning from the glare of my computer screen, I did get to do some travel. And, well, let’s just say my expectations were managed.

Expectation: Jetting off to places like New York, Paris, or some exotic island.

Reality: Paris, Texas; Texarkana, Ark.; and backroads Mississippi.

Expectation: Wearing fancy dresses and business suits while traveling.

Reality: Wearing jeans that can get mud on the butt or cow spit on the legs.

Expectation: Going to parties, perhaps on the beach, sipping champagne cocktails as the breeze blows through my hair.

Reality: Conferences where we eat barbecue or cheap Mexican food while learning the perils of being sucked into a grain bin. If the event is outside, bug spray is optional.

Expectation: Nice cars to escort me around.

Reality: Old trucks that smell like dirt, bumping through pastures and down gravel roads.

Expectation: Writing a story about the locals in a quaint city like Charleston.

Reality: Writing about some farmer taking me to the “bottomlands by the river.”

Expectation: High heels (which I did wear in the office.)

Reality: Ten-year-old Doc Martens that have seen their fair share of cow manure and hay—often mushed together.

Expectation: Well-groomed dogs lying at the entrance of some charming shop.

Reality: A farm dog with blood running down his face because he got in a fight with a neighboring farm dog.

Expectation: Manicured hands.

Reality: Hand licks from the sandpapery tongues of cows.

Expectation: Press releases from four-star resorts and spas.

Reality: E-mailed photos of a mobile semen lab for cows.

Expectation: Samples of new products in shops.

Reality: Sample patches of jeans from Dickies, along with the offer of a desk-side workshop tool demonstration.

Expectation: Coffee table books on architecture.

Reality: Farm office books on the joys of keeping farm animals and growing oats.

Expectation: Travel impediments like hurricanes or snowstorms.

Reality: Electric fences, unruly cattle, and machinery that can eat you to pieces.

Expectation: Flight itineraries to exciting locations.

Reality: A cow’s flight zone (basically how to herd them through a corral using their line of vision).

Expectation: Touring a family’s home and writing about the décor.

Reality: Touring a milking barn and commenting on the farm hands who are artificially inseminating cows. Said workers also are riding around on a golf cart painted like a cow, with semen tanks on it.

Expectation: Well-groomed business people.

Reality: Farmers wearing their names on their shirts.

Expectation: Interviewees waxing poetic about their homes.

Reality: Interviewees complaining about commodity payments and corn prices.

Expectation: Walking down a cobblestone-lined street having just drunk a cup of coffee.

Reality: Sweating off the morning’s caffeine while wandering down a row of corn, trying not to get a paper cut on the leaves, and watching out for frogs.

Expectation: The latest products to review.

Reality: The latest herbicides and fertilizer brands.

Expectation: Gift boxes full of gourmet food.

Reality: A 50-pound bag of specialty horse feed.

So it’s not all wine and roses (okay, not even close), but I’ve perched on the viewing deck of the Eiffel Tower before (unrelated to work), camera aimed at the city below. And while trips like that are indeed a dream, walking through a pasture matching strides with a farmer responsible for nourishing the country is a different kind of dream. And listening to their stories while overlooking a sun-baked field of fluttering cornstalks, it’s easy to forget about that sandy beach. It’s a different job, sure, but a reality and a privilege I wouldn’t trade for anything.

Posted by Deborah Huso on Jul 28, 2014 in

Musings,

Success Guide,

Travel Archives This special post is part of a writer’s blog tour in which I was invited to participate by friend and fellow author Erin Casey. Check out why she writes, and then be sure to check out the blogs of a few other of my favorite bloggers at the end of this post!

The author in her “summer office”

More than a decade ago, when I was just beginning to launch my career as a full-time freelance writer, I remember driving through Goshen Pass in western Virginia, pulling off the road periodically to frame scarlet sugar maples and golden poplars in my camera lens for a fall getaway article I was writing. Still giddy at the idea I was actually pursuing this crazy dream of mine to live by the written word, I turned to my travel companion, a friend who had accompanied me on so many of these writing journeys, and said, “You know what? I’m a writer. I’m actually a writer.”

He regarded me with understandable puzzlement and said, “Well, of course, you’re a writer.”

“No, really,” I insisted, as if daylight had suddenly shattered through the sodden tree limbs overhanging Route 42, “I’m a writer. I’m actually making a living by writing.”

Of course, this was not news to my friend. But somehow it was news to me. Through late nights at the computer and endless prospecting for freelance work, I had somehow been so caught up in the business of making a living by my craft that I had failed to notice the point at which I actually became a professional writer.

But then the question remains, what exactly is a writer? And have I, for the past 30 years, been selling myself short because I was not, for nearly 20 of those years, earning a living wage as a writer? How many writers, after all, can earn a consistent living wage by their craft? After all, it took me two decades to figure it out.

You see, I was not suddenly a writer while photographing autumn foliage in Goshen Pass. Nor was I suddenly a writer when I published my first newspaper article or my first short story. If we want to talk about writing and what it means to be a writer, well then, I have to go back much farther, to a period that doesn’t appear on my resume. Because I have been a writer almost since I could hold a pen, quite literally.

I wrote my first short story when I was six years old. I was no child prodigy. I had been reading biographies of famous Americans written for young children and had loved them so much I wanted to write my own. So I wrote a story (though I probably considered the effort great enough at the time to be called a book) about a pioneer girl named Ellen Kay Brown. And I illustrated it, too, with pencil sketches of girls in bonnets and fathers with grisly beards.

I handed the notebook-paper story to my mother, a high school English teacher, for my first critical review. She didn’t paste it to the refrigerator with a magnet or smile and exclaim how proud she was of my effort. She took it in her hands quite seriously, as she would a research paper on Hamletor Macbeth, and, red pen in hand, proceeded to critique my first attempt at literature, circling my childish “enuff” and changing it to “enough,” capitalizing proper nouns, inserting punctuation.

Was this some cruelty on her part? I never for once thought so, but perhaps some more indulging parent might. This was par for the course in a household where books lined shelves in rooms upstairs and down and where anyone of blood relation would know the difference between “can” and “may” as well as “lie” and “lay.”

I took my little manuscript back, absorbing her red corrections, recording their sense for the next effort, and thus began a ritual between us that lasted until I left home for college. I wrote; she critiqued quietly with her red pen. By the time I graduated from high school, I was one of only a select few in the world who knew, as if by second nature, when and when not to use commas as well as how to give stylistic flair to an exam essay (though my mother claims no responsibility for the latter skill).

Today my mother keeps all these carefully reviewed manuscripts—penciled short stories, illustrated poems, carefully typed essays—in a cabinet in the library. They are small treasures to her, the woman who said, when I declared at six years of age that I was going to be a writer, “It’s never wise to count your chickens before they hatch.”

But I’ve always been counting chickens, hatched and unhatched, and I’ve never assumed anything other than success. That has been my way. It would have to be my way. Only a dreamer could ever believe it possible to make a career out of language.

But still the question—when did I become a writer? My first sense that I might be one actually came when I was a senior in college and my mentor and three-time history professor said upon reading my senior thesis, “There’s nothing I can tell you about writing. I wouldn’t know how to critique you.” My mother never said this, but on the infrequent occasions when I showed her a college or graduate research paper, she would read it, first page to last, hand it back, and say only, “Looks fine to me.” Flipping through the paper, I scanned the pages for the familiar red ink—nothing. Full circle at last, I thought.

Yet no writer who is a good writer ever thinks his or her work is good enough. I read articles I wrote only months ago and think today they look horrible. I have become my mother minus the red pen. All things can be improved upon.

Yet all writers know this, and all writers know, deep down, that it is not so much the paycheck that justifies them as authors. It is the constant development, the constant effort. I have been a writer since I was six. An editor might be intrigued to know that I have more than three decades of experience. But would that intrigue persist if she knew the whole truth?

Probably not.

And that is the sad reality of the writing life. Until you have a paycheck from a publisher, and preferably several, you are not a writer. Your skill level, your decades of practice, your passion are irrelevant . . . at least to most editors.

Did you ever notice that the editor who constantly sent you rejections of your pitches suddenly changed his tune when one of his colleagues took a chance and published your work . . . with success? Yes, once you have a few publishing credits behind you, the rejections trickle to a minimum. Which makes you wonder—does good writing count for anything? Or are editors, like movie producers, tied to the tried and true?

Well, yes and no. Good writing does count for something. After all, it’s easier to publish good writing than bad. But getting good writing noticed, in the end, is a matter of luck. For myself, I ran into an overwhelmed newspaper editor willing to take a chance on me and the editor of a start-up lifestyle magazine with a dearth of authors. After that, everything began to fall into place. Just ask Nicholas Sparks how he became a best-selling author overnight. His answer, like that of so many other wildly successful writers, will make you dream like the daily players of the lottery and gnash your teeth at the same time.

It is luck.

But it’s also persistence. Beat the statistics by flooding the market.

I guess my mother, my original editor, knew a thing or two. I kept passing her the notebook paper, and one day it came back without red ink. Was it talent, or did I beat the odds? Perhaps a little of both . . . but maybe it’s time I started playing the lottery.

Check out some more writer’s blogs on this tour. Below are three of my favorite writer ladies!

Susannah Herrada is an aspiring “Lady who Lunches” who spends most days trying to figure out how to avoid the mundane inherent in her role as ‘homemaker’ by preparing for or unpacking from an adventure. Spending about a quarter of her life on the road these past few years, she’s anything but a ‘stay at home mom.’ For summer 2013, she’s on her third extended summer trip, this time to Central America, two kids in tow.

Susannah Herrada is an aspiring “Lady who Lunches” who spends most days trying to figure out how to avoid the mundane inherent in her role as ‘homemaker’ by preparing for or unpacking from an adventure. Spending about a quarter of her life on the road these past few years, she’s anything but a ‘stay at home mom.’ For summer 2013, she’s on her third extended summer trip, this time to Central America, two kids in tow.

Check out her wanderings at Not At Home Mom. After each trip, she finds herself back in the Washington D.C. metro area with a new perspective on life, love, parenting, politics, and what really matters.

Before Susannah turned her sights to the open road (and writing about it), she taught eighth grade physical science in Arlington, Virginia.

Mollie Cox Bryan is a journalist and cookbook author turned novelist. After 20 years of writing nonfiction for nonprofits, corporations, museums, magazines like Grit, Taste of the South, and NPR’s Kitchen Window, and cookbooks, she turned to mystery. Scrapbook of Secrets: A Cumberland Creek Mystery (Kensington, 2012) was her first mystery novel and was an Agatha Award finalist for best first novel in 2012. Her second in this five-book series,Scrapped (Kensington, 2013), is a finalist for the Library of Virginia’s People’s Choice Literary Award.

Mollie Cox Bryan is a journalist and cookbook author turned novelist. After 20 years of writing nonfiction for nonprofits, corporations, museums, magazines like Grit, Taste of the South, and NPR’s Kitchen Window, and cookbooks, she turned to mystery. Scrapbook of Secrets: A Cumberland Creek Mystery (Kensington, 2012) was her first mystery novel and was an Agatha Award finalist for best first novel in 2012. Her second in this five-book series,Scrapped (Kensington, 2013), is a finalist for the Library of Virginia’s People’s Choice Literary Award.

The mother of two active daughters, Mollie lives in Waynesboro, Va., where her traveling consists of carting the girls back and forth to music and dance classes, the library, and shopping malls. Visit Mollie’s blog about the writing life.

Jill Smokler is New York Times bestselling author of Confessions of a Scary Mommy (Simon and Schuster, 2012) and Motherhood Comes Naturally (And Other Vicious Lies) (Simon and Schuster, 2013). She runs The Scary Mommy web site, an online confessional of sorts about motherhood and oversees Scary Mommy Nation, a 501(c)3 organization devoted to helping Moms in a really scary situation–the inability to feed their families.

Check out the Scary Mommy blog!

Posted by Deborah Huso on Jun 18, 2014 in

Men,

Relationships,

Success Guide

The sport I took up for a guy….

Originally published March 22, 2012.

I’ll admit it. I’ve done a few crazy things for men. Like pretending to enjoy watching a boyfriend participate in some bizarre World War I re-enactment that actually involved mud and trenches but really looked like a bunch of grown men playing dress-up in the great outdoors.

Then there was the boyfriend who tried to teach me fly fishing. (Why I agreed I’ll never know, as I consider standing in a stream or at lake’s edge with a fishing pole about as exciting as watching paint dry.) But I tried it nevertheless. I wasn’t at it five minutes before I had my line tangled in a crabapple tree.

And I must not fail to include hanging out in the pit at a race track, the dirt from the track flying so thick that it later took two showers to get all the grit out of my ears and several flossings to get it out of my teeth. Not to mention the two beer guzzling guys who walked past me, saying, “Dude, I bet we’ll find some hot women here tonight.” (I should probably mention my S.O. at the time was a race car driver, not a spectator, which basically means he did not own a T-shirt with a Confederate flag on it with the sleeve rolled up on one side to show off the tattoo of his mother’s first name.)

True, I’m not very P.C. I can’t help it. I call it like I see it.

Which is why I feel compelled to point out that I quickly learned we should all have our limits. Mine was one re-enactment and two dirt track races. (I liked the second guy better.) And I’m inclined to think, now that I’m older and wiser, that my limits might be even more stringent these days. A guy would have to be Mr. Wonderful for sure to get me to bungee jump off a bridge in New Zealand. Basically, he’d half to be flawless. And I’m still not sure I’d do it.

So I kind of wonder why women do so many crazy things for men. Are we really that desperate? So desperate to hold their interest and affection that we take up their crazy hobbies or at least stand on the sidelines watching them with enough regularity that we start to look a little bit…well…desperate.

Learning archery in the Ozarks

It hit home with me the second (and last) race I attended. Somehow I had convinced myself I was being supportive by spending a lovely spring weekend driving God knows how many hours through central North Carolina (the armpit of the state, in my opinion, with all its look-alike cities, interstates, and giant junk outlets) to the dirt track in Gastonia in a really big pick-up towing a sprint car (which if you don’t know what that is, ladies, it’s the one with the really big rear wheels and the Orville Wright-esque roof that makes it looks like a cross between an airplane and a go-cart). I spent most of the day in the pit sitting on a tailgate reading a biography of William Faulkner for an article I was writing while the wives and girlfriends of the other race car drivers dished out elaborate buffets of fried chicken and biscuits, tested all their video recording equipment, and began climbing up on the roofs of their S.O.’s six-figure price tag towing vehicles to see if they could videotape the races from there. When race time rolled around, each one of those ladies lined up alongside her husband’s car, his helmet in hand like a squire waiting to tend to a knight. That was the point at which I started to feel weird and decided the so-called fine line between being supportive and being pathetic was actually not so fine after all.

After that episode, I showed my support by not raising hell on the weekends my boyfriend decided to spend at the track and stayed home where there were much more interesting things to do than fawn over a weekend warrior race car driver.

But I’m not alone in having made some ridiculous efforts to impress a man with my supportiveness. A friend of a friend who was planning a romantic getaway to Hawaii with her fiancé recently relented when he suggested they go camping in Utah instead…in a Winnebago…a very old Winnebago. Driving cross-country for three days, camping for five, then driving back. And in the interim, their meals would be tuna out of a can and the romance would be lovemaking in the back of a van. Sure, it’s a little reminiscent of the teenage years in a way, but who wants to make out in a stinky van at age 40? I’m personally all for the luxury hotel mattress.

I’m sure the lady in question is, too, so why won’t she admit it, hold firm, and buy those plane tickets to Hawaii?

Yeah, you guessed it. For some reason, she feels that in order to hang onto the guy she has to sacrifice her sanity…and her precious vacation time. You might be desperate if you do this, ladies.

Kayaking along the Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore

Another friend of mine has an even more interesting track record. In the course of her relationship career, she has purchased a bass boat, a motorcycle, and a kayak. She still has the kayak, and I think she actually uses it, but the bass boat and the motorcycle have long since hit the pavement. I’m not even sure she actually ever got on the motorcycle. The purchase, I think, was a gesture of intent.

And apparently good intentions work, as she did marry the guy. He goes duck hunting and motorcycling without her these days, much to her relief, no doubt.

Women may claim that men, once married, suddenly forget how to cook, dance, and kiss, but women are guilty, too. Our “tactics of desperation,” as I like to call them, suddenly cease once we feel we have the guy cornered. We magically lose interest in skeet shooting, football, and black lingerie. (Well, some of us do anyway. Personally, I would never want to be caught in Grandma panties by an EMT following a traumatic car accident, and I do know a woman who makes cupcakes with her husband’s picked team’s logo emblazoned in the frosting for the Super Bowl each year.)

A friend of mine actually asked me to write this post after deciding a couple of her women friends were acting a little too “desperate.” At the time, I agreed with her that there are just some things you don’t do for a man, any man.

But then I got to thinking about it and, pathetic Super Bowl cupcakes aside, all this stretching of ourselves beyond normal limits isn’t necessarily a bad thing, not always. Sometimes acts of desperation turn out all right. I would never have discovered a love of sea kayaking had my former husband not goaded me into trying it out off a sandy beach in St. Croix. Nor would I have learned how to shoot had a boyfriend not introduced me to the sport more than a decade ago and enticed me to at least learn how to blast a rabid skunk…or a rabid neighbor…if I needed to. And frankly, I think if I’d been permitted a spin around the racetrack (instead of standing on the sidelines), I might have found that a little bit more interesting, too.

This is not to say I’m encouraging acts of female desperation, which seem to be most common in the unknowing years of the early 20s and the “oh, my god, I am never gonna get married unless I take up skydiving with this guy” years post 40. It’s okay to get your feet wet in something new, just so long as you’re not sacrificing your own sense of self to do so or stretching limits that you’ve put in place for very good reasons. Moving in with an S.O. who owns 12 indoor dogs when you are a stickler for cleanliness is not likely to do anything for expanding your horizons or enhancing your relationship. This is a guy it’s even questionable whether or not you should be dating him much less marrying him (I mean does he ever show up without dog hair on his pants?). Nor should you drink tuna water in the back of a Winnebago if every part of your being is screaming for a relaxing, luxurious getaway on a Pacific beach. Resentment isn’t something you want to cultivate in a relationship either.

But you do want to cultivate growth.

Rest assured, however, the line between growing and being desperate is very thick and very black. You can’t miss it.

Growth feels like a rush. Desperation feels like anxiety. (Given how few men are willing to learn ballroom dancing and yoga, however, I’m guessing they feel a lot more anxiety about trying new things than we do.)

I’ve found as I grow older, I don’t really need the goading of a romantic partner to incline me to try something new…unless it’s squid. Not really inclined to try that on my own, though I did recently eat some wild boar. I’ll gladly make a vain attempt at doing yoga on a paddleboard in the Tennessee River or see how much I can embarrass myself on an archery range in the Ozarks just because I can (and because an editor is paying me to do it). It seems appropriate, once mid-life starts its heavy approach, to be up for anything.

With a couple of exceptions….

I still don’t plan to bungee jump off the New River Bridge anytime soon. Nor will I go ZORBing. Something about intentionally cramming one’s self into a rubber ball and then having someone push it down a hill at breakneck speed just seems…well…stupid. And I really don’t feel either activity is going to promote any personal or spiritual growth…unless we’re talking a very quick trip to heaven.

But there are definitely experiences that you shouldn’t pass up. Years ago when a friend of mine went horseback riding in the snow in Iceland with her boyfriend, I thought she had lost her mind. Today she’s married to the guy and has, with his encouragement, hit five continents in the last decade and a half. Talk about “desperation” paying off. Maybe fly fishing isn’t your thing. But I bet, even if it’s not, that standing in the middle of the Madison River in northwestern Wyoming with a moose grazing nearby and the Rockies rising in the distance has the potential to float your boat…even if next time you come armed with a camera instead of a fishing rod.

Posted by Deborah Huso on May 12, 2014 in

Musings,

Relationships,

Success Guide Originally published May 20, 2013.

There are wonderful times when life catches me completely off guard. Like a week ago when I attended my five-year-old’s first piano recital. It was, initially, reminiscent of the recitals I’d played in as a child, where the first children to play were the youngest and least skilled, and the last were those who could show some mastery over their lessons. Needless to say, I never played last at a recital in any of my seven to eight years of piano lessons. I liked playing the piano, still do, but I was never passionate about it.

However, last Sunday, I saw passion. As I sat there in church watching one student succeed another, a few of them showing fine technical skill, I expected no great epiphanies at the keyboard. But then the last student to play, an 11-year-old boy who had been taking lessons only four years, sat down to regale the audience with five minutes or so of “Pirates of the Caribbean,” and I sat there dumbfounded. Not only did this boy demonstrate technical skill way beyond his years, but he played with the passion of a man who has found and lost love, watched a beloved die, walked through fire….

Where does feeling like that come from in an 11-year-old boy?

I have no idea.

But I do know that it was not passion alone that made that young man stroke the keys as if he was born to play. The piano teacher’s sister informed me after the recital that the boy’s parents could hardly keep him from the piano, that he played all the time.

That’s not just passion. That’s commitment.

And if you ever want to succeed at something, and I mean really succeed, you have to have both.

How often have I seen a person with passion for an art, skill, or subject fail to reach potential, not for lack of talent but for lack of commitment. And commitment, mind you, is more than hard work. It comes with cost and sacrifice.

A friend of mine had to give a meditation recently at a wedding, and she was anxious about how to do it because she had been asked not to be too religious. “How can I talk about passion,” she asked, “and not draw an anomaly to the passion of Christ?”

I don’t know what she ultimately came up with, but even though I’m not religious, I know there is much to learn from what we refer to as “Christ’s passion.” Jesus, whether mortal or God, was willing to take the cost, make the ultimate sacrifice, for what he believed. The result? His life and teachings form one of the world’s most influential religions. And that’s really just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the influence of Jesus’ passion and commitment.

I suspect, knowing my friend, that she perhaps touched on the necessity of passion and commitment to a successful marriage. It is one thing to love another person, even deeply love him. It is quite another to commit yourself to maintaining that love for life. That not only takes work, like the work of resolving minor disputes before they become big resentments, but the work of sacrifice–willingly and lovingly giving up to get more. And I don’t mean more in a greedy sense. I mean more fulfillment, more meaning, and, ultimately, more passion.

Because that’s the thing about commitment that is passion-inspired. It builds more passion.

I will not pretend to know about passion and commitment within the framework of a marriage. I know I tried commitment without passion for a very long time, and it didn’t seem to do much other than take up valuable space in the short span of what we know as life.

But I do know about passion in other things. I have had a passion for writing since I was a small child, yet for a brief period while in college and grad school, I let a couple of mentors convince me to pursue a career as professor instead of as a writer. To my good fortune, poverty eventually drove me out of academe, and I began to see, after working as an ex parte brief writer, speech writer, and copywriter, that one could indeed earn a living writing.

For five years, I spent every waking hour I wasn’t at my salaried job working to build my own business as a writer. And once I cut the cord to the world of the regular paycheck and began freelancing full-time, I worked 80-hour weeks for a couple of years to build a client base. There was never a time that any of it felt exhausting. Why? Because I was passionately committed to living my dream.

The same held true when I finally bought the farm I’d always dreamed of owning and built the house I’d always dreamed of building, working until the wee hours of the morning at times painting cathedral ceilings while lying on my back on a scaffold, hanging wallpaper, and sanding and varnishing cabinets, stair treads, and trim. Passion launched me. Commitment held me.

I have no doubt I will hear one day of that 11-year-old boy at my daughter’s piano recital rocking the world stage as a concert pianist. Because the boy is not just passionate; he is committed. He practices his passion daily.

That’s the key—daily commitment to passion.

As one of my favorite poets, Pablo Neruda, remarks, you should live “as if you were on fire from within.” Doing anything less is not really living; it is not really committing. If you believe in your passion, whether it is the passion you hold for your work or the passion you hold for your lover, then commit to it, live as if “the moon lives in the lining of your skin.”

There are good reasons for this. Belonging means survival. Not just in nature. Even in civilized life. It’s such a deep, primal fear that many of us choose being miserable in a group, in a relationship, in a family, merely to avoid that dark chasm known as being alone.

There are good reasons for this. Belonging means survival. Not just in nature. Even in civilized life. It’s such a deep, primal fear that many of us choose being miserable in a group, in a relationship, in a family, merely to avoid that dark chasm known as being alone.

Mollie Cox Bryan is a journalist and cookbook author turned novelist. After 20 years of writing nonfiction for nonprofits, corporations, museums, magazines like Grit, Taste of the South, and NPR’s Kitchen Window, and cookbooks, she turned to mystery. Scrapbook of Secrets: A Cumberland Creek Mystery (Kensington, 2012) was her first mystery novel and was an Agatha Award finalist for best first novel in 2012. Her second in this five-book series,Scrapped (Kensington, 2013), is a finalist for the Library of Virginia’s People’s Choice Literary Award.

Mollie Cox Bryan is a journalist and cookbook author turned novelist. After 20 years of writing nonfiction for nonprofits, corporations, museums, magazines like Grit, Taste of the South, and NPR’s Kitchen Window, and cookbooks, she turned to mystery. Scrapbook of Secrets: A Cumberland Creek Mystery (Kensington, 2012) was her first mystery novel and was an Agatha Award finalist for best first novel in 2012. Her second in this five-book series,Scrapped (Kensington, 2013), is a finalist for the Library of Virginia’s People’s Choice Literary Award.